Key points

- Dementia can impact thinking, behaviour, language, memory, personality, and the ability to perform everyday tasks.

- Some technologies are specifically integrated into aged care settings to increase support or improve the quality of life for people living with dementia.

- There are concerns that the integration of technology may violate the privacy and dignity of people with dementia or have the potential to reduce meaningful interaction with other people.

- The focus of much of the research on technology and dementia care is on robotic pets. These studies suggest that many older adults and aged care staff accept and embrace robotic pets, although some individuals express concerns about the integration of robots into aged care settings.

Dementia is a syndrome (a collection of symptoms) caused by disorders impacting the brain. [1] It can affect thinking, behaviour, language, memory, personality, and the ability to perform everyday tasks. [1] Over time, a person with dementia may steadily become reliant on support from others. [2] Aged care is currently in a period of rapid change and integration of technology is a critical part of this change. Some technologies are introduced specifically to increase support or improve the quality of life for people living with dementia. However, some technologies may be introduced into aged care settings with limited consideration of those with cognitive decline. [3]

This evidence theme on technology and dementia is a summary of one of the key topics identified by a scoping review of technology in aged care research. We identified 17 papers on this topic. Included studies focused on a variety of technologies, including robotic pets [4-8], virtual reality [9-13], surveillance [14], teleoperated humanoid robots [15], virtual cycling [16], digital monitoring technology [3, 17], objects created with 3D printers [18], an interactive pet/avatar/surveillance program, [19] and robotics and autonomous systems. [20] If you require more information on the topic of technology and dementia, try using our PubMed searches provided below.

Privacy and dignity

Some studies highlighted concerns about whether the integration of technology may violate the privacy and dignity of people with dementia. While we have covered the topics of privacy and safety, and maintaining dignity in separate evidence themes, there are additional considerations for people living with dementia which we will briefly discuss here.

Concerns about privacy and dignity were particularly high when it came to monitoring technologies such as cameras and surveillance systems, or robots that can gather information about the older person. [14, 19-21] There are complex issues surrounding the collection of information about people with dementia who may not always be aware of the information being collected (or the extent of information being collected) despite consent being provided by themselves at an earlier time, or by their loved ones. [19, 20] Privacy was a major concern among family caregivers when deciding whether certain technologies might benefit themselves or their loved one with dementia. This concern was especially present when people had more advanced dementia. [21] However, in one study, participants who expressed concerns about the privacy of their loved ones sent in as much data as those who did not express these concerns. This may indicate that the need for support outweighed concerns for privacy. [21]

Virtual reality

Another focus of the literature was the use of virtual reality (VR) among people living with dementia. Please see our separate evidence theme on engagement with virtual reality which includes the perspectives and experiences of people living with dementia.

Robotic pets

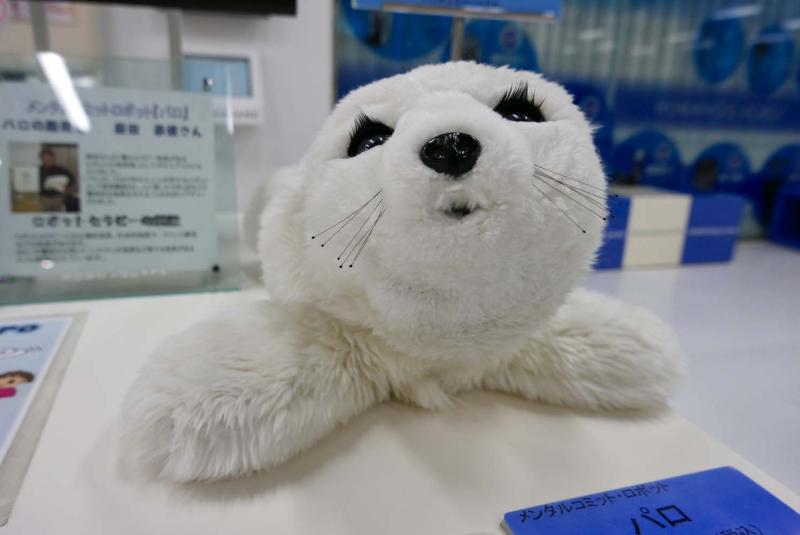

There were multiple papers focused on the use of robotics for people living with dementia. Overall, people living with dementia reported positive perceptions of robots, particularly robotic pets. [4-8] The papers mostly focused on a robotic harp seal named Paro. [6, 8] Paro can interact with people by opening and closing its eyes, moving its neck and flippers, or making sounds when it is being stroked. [8] For more information about general attitudes towards robots in aged care, see our attitudes towards robots theme.

The literature focusing on the perceptions of people living with dementia and/or their families towards robots suggested that:

- Older people had generally positive attitudes toward Paro’s appearance and its interactivity. [8]

- Some people with more advanced dementia perceived Paro as a real animal (such as a puppy). This could potentially prompt memories and conversations about their past. [8]

- Some people knew Paro was a toy but treated it as a real animal and reported that it could provide them with comfort. [8]

- Paro was perceived as being friendly, with older adults describing the robot as ‘warm’ and ‘pleasant’. Some people said they felt as though Paro was a ‘friend’ they could talk to who looked like he was ‘listening’ to them. [8]

- Participants reported that Paro made them feel safe, relaxed, happy and calm. [8]

- Participants perceived that Paro might be beneficial for mood improvement and for pain relief (due to relaxation). [8]

- Paro was perceived as potentially useful for people who were limited in their ability to engage in activities. [8]

- Participants reported that they enjoyed being able to hug and pat the robot. [8]

- Some stated that Paro was too heavy, made noises that could be confused as cries, and that they would like the robot to be more animated. [8]

- People with moderate dementia were more likely to interact with robots in general than people without dementia or with mild dementia. [5]

Some studies focused on how staff perceived robots in aged care settings. Findings show that staff:

- Are willing to adopt Paro as a companion animal for people living with dementia [7], with some staff saying it was ‘convenient’, and a ‘wonderful support’. [4]

- Perceived that Paro had benefits and found it useful and practical for people living with dementia to use. [7]

- Perceived that residents chatted to Paro, and this gave them the confidence to talk with others around them. [7]

- Reported that Paro may present a good opportunity for distraction from distress or pain and for feelings of engagement, especially for those whose families did not visit often. [7]

- Expressed concerns that people living with dementia may not be able to communicate or display when they do not want to engage with Paro. [7]

- Appreciated that Paro was low maintenance, clean, doesn’t require feeding, and doesn’t make a mess. [7]

- Believed that Paro could provide opportunities for people to reminisce about their past. [7]

- Reported that men and women responded relatively well to Paro. This contrasts with other objects such as toys or dolls which staff reported that men are less likely to show interest in compared to women. [7]

- Could be concerned that robot pets could be infantilising to older adults. However, some staff perceived that compared to plush toys, robot pets were not as infantilising. [7, 20]

- Expressed concerns about technology replacing human contact. [20] For some individuals, particularly those with dementia, gesture and touch may be relied upon as a form of communication. An over-reliance on robots may result in deprivation of human contact which may negatively impact the health and wellbeing of older adults. Staff say in many situations, technology cannot and should not replace human contact. [20] See our evidence theme on quality of human interaction for more on this topic.

The studies included in our review suggested several factors that may be important to consider when introducing a new technology.

- Keep in mind that all individuals are unique and consider how different approaches may benefit different people. For example, some people may benefit more from interventions in a group setting, and some may prefer to engage with technology on their own or with one-on-one support from staff. [7, 15]

- Understand that, while virtual reality is becoming increasingly popular, the use of a large screen may also be an immersive experience without the need for VR headsets, which may be uncomfortable or distressing for some individuals. [16]

- Introduce technologies in environments where people already feel comfortable and familiar. [16]

- Be aware that some product developers and/or information technology staff have limited knowledge about dementia and the needs of people living with dementia. [3]

- Provide staff with a list of prompting questions if engaging with technology aimed to prompt reminiscence. [18]

- Consider any movement limitations an individual may have when introducing them to a technology. [11]

- Always consider the preferences of each individual. [8]

- Keep in mind that how older adults respond to technologies may fluctuate over time. [8]

- Dementia Australia. About dementia [Internet]. n.d. [cited 2023 Jun 26]. Available from: https://www.dementia.org.au/about-dementia/what-is-dementia

- healthdirect. Supporting carers of people with dementia [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2023 Jun 26]. Available from: https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/supporting-carers-of-people-with-dementia

- Dugstad J, Eide T, Nilsen ER, Eide H. Towards successful digital transformation through co-creation: A longitudinal study of a four-year implementation of digital monitoring technology in residential care for persons with dementia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):366.

- Abbott R, Orr N, McGill P, Whear R, Bethel A, Garside R, et al. How do "robopets" impact the health and well‐being of residents in care homes? A systematic review of qualitative and quantitative evidence. Int J Older People Nurs. 2019;14(3).

- Bradwell H, Edwards KJ, Winnington R, Thill S, Allgar V, Jones RB. Implementing affordable socially assistive pet robots in care homes before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: Stratified cluster randomized controlled trial and mixed methods study. JMIR Aging. 2022;5(3).

- Fogelson DM, Rutledge C, Zimbro KS. The impact of robotic companion pets on depression and loneliness for older adults with dementia during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Holist Nurs. 2022;40(4):397-409.

- Moyle W, Bramble M, Jones C, Murfield J. Care staff perceptions of a social robot called Paro and a look-alike plush toy: A descriptive qualitative approach. Aging Ment Health. 2018;22(3):330-335.

- Pu L, Moyle W, Jones C. How people with dementia perceive a therapeutic robot called Paro in relation to their pain and mood: A qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(3-4):437-446.

- Appel L, Appel E, Kisonas E, Lewis S, Sheng LQ. Virtual reality for veteran relaxation: Can VR therapy help veterans living with dementia who exhibit responsive behaviors? Front Virtual Real. 2022;2.

- Baker S, Waycott J, Robertson E, Carrasco R, Neves BB, Hampson R, et al. Evaluating the use of interactive virtual reality technology with older adults living in residential aged care. Inf Process Manag. 2020;57(3).

- Muñoz J, Mehrabi S, Li Y, Basharat A, Middleton LE, Cao S, et al. Immersive virtual reality exergames for persons living with dementia: User-centered design study as a multistakeholder team during the COVID-19 pandemic. JMIR Serious Games. 2022;10(1).

- Chaze F, Hayden L, Azevedo A, Kamath A, Bucko D, Kashlan Y, et al. Virtual reality and well-being in older adults: Results from a pilot implementation of virtual reality in long-term care. J Rehabil Assist Technol Eng. 2022;9:20556683211072384.

- Brimelow RE, Dawe B, Dissanayaka N. Preliminary research: Virtual reality in residential aged care to reduce apathy and improve mood. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2020;23(3):165-170.

- Berridge C, Halpern J, Levy K. Cameras on beds: The ethics of surveillance in nursing home rooms. AJOB Empir Bioeth. 2019;10(1):55-62.

- Chen LY, Sumioka H, Ke LJ, Shiomi M, Chen LK. Effects of teleoperated humanoid robot application in older adults with neurocognitive disorders in Taiwan: A report of three cases. Aging Med Health. 2020;11(2):67-71.

- D'Cunha NM, Isbel ST, Frost J, Fearon A, McKune AJ, Naumovski N, et al. Effects of a virtual group cycling experience on people living with dementia: A mixed method pilot study. Dementia (London). 2021;20(5):1518-1535.

- Hall A, Brown Wilson C, Stanmore E, Todd C. Moving beyond ‘safety’ versus ‘autonomy’: A qualitative exploration of the ethics of using monitoring technologies in long-term dementia care. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):145.

- Garlinghouse A, Rud S, Johnson K, Plocher T, Klassen D, Havey T, et al. Creating objects with 3D printers to stimulate reminiscence in memory loss: A mixed-method feasibility study. Inform Health Soc Care. 2018;43(4):362-378.

- Portacolone E, Halpern J, Luxenberg J, Harrison KL, Covinsky KE. Ethical issues raised by the introduction of artificial companions to older adults with cognitive impairment: A call for interdisciplinary collaborations. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;76(2):445-455.

- Tan SY, Taeihagh A, Tripathi A. Tensions and antagonistic interactions of risks and ethics of using robotics and autonomous systems in long-term care. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2021;167.

- Williams KN, Shaw CA, Perkhounkova Y, Hein M, Coleman CK. Satisfaction, utilization, and feasibility of a telehealth intervention for in-home dementia care support: A mixed methods study. Dementia (London). 2021;20(5):1565-1585.

Connect to PubMed evidence

This PubMed topic search is focused on research conducted in aged care settings (i.e., home care and residential aged care). You can choose to view all citations or free full-text articles.